Pop, Rock, Country, Damnation

I was talking with a friend about a discussion he's having in a class, comparing "Bohemian Rhapsody" with "The Devil Went Down To Georgia." Some nice parallels and contrasts, yes?

For one thing, beyond the witty wordplay and drastic moral scheme, both use overdubbing to create an overwhelming sense of 'legion' in the spiritual plane: with Queen it's voices, and with the Charlie Daniels Band it's the Devil's multi-voiced stereo-riffic violin.

Both include pastiche of a different musical style —– no doubt both groups relished showing off their skill in doing it, though the Charlie Daniels Band accomplishes a convincing funk groove whereas Queen goes more for the cartoon version of classical music (and neither is very authentic). Interestingly, both versions represent the music of the spiritual plane as a familiar but Not-Us style —– kind of like how Disney always has the good guys speaking with "our" accent and the bad guys speaking with a foreign one. (The Arab Aladdin speaks with a middle American accent, while the Arab Jafar with a British one! —– interesting, because in the 1001 Nights, of course, the whole tale takes place in China.)

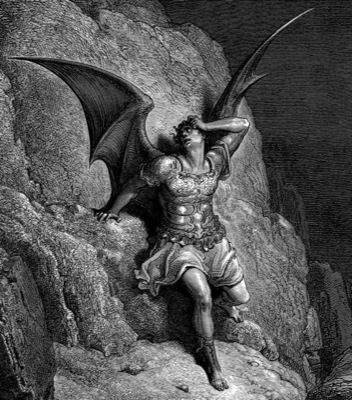

Then there are the lyrical texts. Which one is more honest? Is either honest? In one, we have a truly guilt-ridden person who has just committed murder (we're led to believe he killed the man who loved and left him) and is about to commit suicide, imagining, after apostrophizing his ostensibly Catholic mother, a condemnation by comic-Dantean divine jury, helplessly being argued over . . . but then winding up as Manfred, shaking his fist at the heavens and his fellow man as he takes his own life. In the other, a down-home boy with extraordinary gifts who is pictured as making a deal with the Devil and then outdoing him. It's presented as no more than a southern tall tale, but, looking at the implications seriously, is Johnny really better off than [let's say] Freddie?

Is either song taking the moral implications of this life seriously? I'd argue that both are, and both aren't, I guess. Interestingly, the cartoonish "Rhapsody" winds up with a bit more moral seriousness than the folkish "Devil," which, perhaps perilously, pictures the Devil being bested at his own game. We might, though, offer some different interpretations of "Devil": for instance, is Johnny actually a Christ figure, though a superficial one because there's no real sacrifice of self? Or, given the chorus, with its roster of invented comic-folk song references, are we saying that by sticking to what you know and being true to yourself you can indeed best the Devil ("resist him and he will flee")? On a more down-to-earth level it can certainly be read as a music-biz parable, given the state of things in the mid-70s. By representing the devil's music as an infernal form of disco, the song becomes a commentary on the politics of country music in Nashville at the time. Do you remain true to your fiddlin' roots or do you sell out and do country-rock?

The interesting thing here is that neither country nor pop nor, really, rock 'n' roll could have produced either of these songs in the fifties or even sixties. The answer to "what is a song supposed to be about" keeps changing every couple of decades in pop music since the Civil War.

Is there anything a pop song shouldn't address, or can't address, simply because of the limitations of pop music? And is your answer to those questions affirmed or contradicted by the fact that both of these songs approach risky territory wearing the costume of forms that aren't quite so limited (high culture in one case and folk culture in the other)?

Comments