can't talk about this without that, part 4: ethyl

It's inevitable that when you discuss an issue you're probably leaving out some vastly important factor. Counting everything that really counts is so hard, you're bound to miss something. But sometimes it's glaring: no discussion of a piece of music can be complete without at least acknowledging the elements of rhythm, harmony, and melody. (I'm lookin' at you, Rolling Stone.) Sometimes you just have to say you can't talk about this without that.

Crime, for instance. Miles of books have been written about the great rise of violent crime in the US starting in the late 50s, reaching fever pitch in the late 60s and early 70s, rising even further till the late 80s, and then subsiding as dramatically as it rose.

Pages on pages of Malcolm Gladwell's book The Tipping Point are devoted to just this topic, with all sorts of theories put forward about why the sudden drop in crime happened, just when we'd assumed that big cities like New York and Chicago were permanent cesspools of ill behavior and that the complete breakdown of society was on the way.

What most folks don't mention is ethyl.

Fill 'er up.

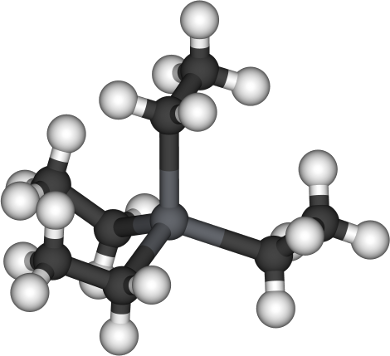

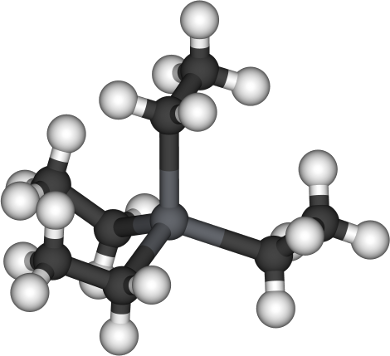

If you were born in 1970ish or before, you remember that that was a kind of premium gas you could get. The three varieties were Regular, Premium, and Ethyl. Ethyl was gas with an additive of tetraethyl lead, a formula invented by GM in the 20s that prevented pinging. In the postwar era, people used more and more of it, until, in the 70s and 80s, catalytic converters and gas prices and environmental awareness made it so people used less and less. I remember feeling a bit sad when Ethyl was no longer available. (Later, I was older and less sad when Regular was no longer used, and the three choices were Regular Unleaded, Super Unleaded, and Premium Unleaded.)

This article leaves no doubt: they've researched it intensively, corrected for all sorts of variables, tested it nationwide (areas where the use of lead in gas was higher or lower than other areas) and worldwide (when and how did other countries start and stop using the stuff), and it's the only variable that makes sense. Whatever other explanation you may have had —– population changes, educational philosophies, economic fluctuations, prison growth or reform —– just can't explain the situation. All over the world, there was a swift rise in violent crime starting around 20 years after it was in the air breathed by babies and children, and then a swift decline right around 20 years after it stopped being in the air breathed by babies and children.

All those old men complaining about "kids today," while driving their Gran Torinos. Ironic.

Further, just for those not convinced, the receding tide of this lead particle in gasoline has meant that lead's presence in other things like old-fashioned paint is more noticeable and measurable, and, sure enough, correlates exactly to violent crime (as well as other interesting things like intelligence and teen pregnancy).

This is all important because of course it should be part of our conversation but often isn't. Any discussion about crime and punishment, especially if it's being conducted by people who came of age during that strange blip in history, is going to be way off-kilter unless this major cause is taken into account. If someone argues that we should be building more prisons, for instance, they need to stop and realize that probably a reduction in prisons would be a better idea, as the decades-long prison sentences that began in the 70s and 80s come to an end. (In relation to violent crime, remember.) Meanwhile, maybe a systematic removal of lead from places where it was deposited (soil in some urban areas, leaded paint in old buildings) would be a better way to spend money that would hasten the demise of lead-influenced ills.

The solution to this puzzle has now been presented to us, with beyond-all-doubt proof. What will we do with that knowledge?

Crime, for instance. Miles of books have been written about the great rise of violent crime in the US starting in the late 50s, reaching fever pitch in the late 60s and early 70s, rising even further till the late 80s, and then subsiding as dramatically as it rose.

Pages on pages of Malcolm Gladwell's book The Tipping Point are devoted to just this topic, with all sorts of theories put forward about why the sudden drop in crime happened, just when we'd assumed that big cities like New York and Chicago were permanent cesspools of ill behavior and that the complete breakdown of society was on the way.

What most folks don't mention is ethyl.

Fill 'er up.

If you were born in 1970ish or before, you remember that that was a kind of premium gas you could get. The three varieties were Regular, Premium, and Ethyl. Ethyl was gas with an additive of tetraethyl lead, a formula invented by GM in the 20s that prevented pinging. In the postwar era, people used more and more of it, until, in the 70s and 80s, catalytic converters and gas prices and environmental awareness made it so people used less and less. I remember feeling a bit sad when Ethyl was no longer available. (Later, I was older and less sad when Regular was no longer used, and the three choices were Regular Unleaded, Super Unleaded, and Premium Unleaded.)

This article leaves no doubt: they've researched it intensively, corrected for all sorts of variables, tested it nationwide (areas where the use of lead in gas was higher or lower than other areas) and worldwide (when and how did other countries start and stop using the stuff), and it's the only variable that makes sense. Whatever other explanation you may have had —– population changes, educational philosophies, economic fluctuations, prison growth or reform —– just can't explain the situation. All over the world, there was a swift rise in violent crime starting around 20 years after it was in the air breathed by babies and children, and then a swift decline right around 20 years after it stopped being in the air breathed by babies and children.

All those old men complaining about "kids today," while driving their Gran Torinos. Ironic.

Further, just for those not convinced, the receding tide of this lead particle in gasoline has meant that lead's presence in other things like old-fashioned paint is more noticeable and measurable, and, sure enough, correlates exactly to violent crime (as well as other interesting things like intelligence and teen pregnancy).

This is all important because of course it should be part of our conversation but often isn't. Any discussion about crime and punishment, especially if it's being conducted by people who came of age during that strange blip in history, is going to be way off-kilter unless this major cause is taken into account. If someone argues that we should be building more prisons, for instance, they need to stop and realize that probably a reduction in prisons would be a better idea, as the decades-long prison sentences that began in the 70s and 80s come to an end. (In relation to violent crime, remember.) Meanwhile, maybe a systematic removal of lead from places where it was deposited (soil in some urban areas, leaded paint in old buildings) would be a better way to spend money that would hasten the demise of lead-influenced ills.

The solution to this puzzle has now been presented to us, with beyond-all-doubt proof. What will we do with that knowledge?

Comments